The lazy-seeming abstraction I was seeing all over Berlin last year has a name: Zombie Formalism.

Robert Mangold’s “Framed Square With Open Center II” , 2013

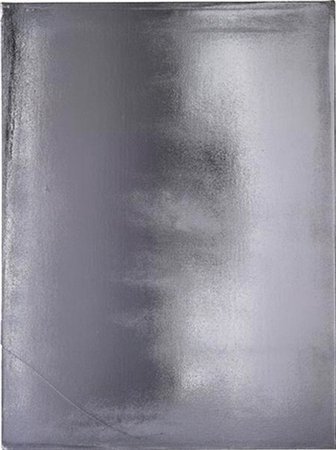

Walter Robinson at Artspace invented the term: "With their simple and direct manufacture, these artworks are elegant and elemental, and can be said to say something basic about what painting is—about its ontology, if you think of abstraction as a philosophical venture. Like a figure of speech or, perhaps, like a joke, this kind of painting is easy to understand, yet suggestive of multiple meanings. (Kassay’s paintings, for example, are ostensibly made with silver, a valuable metal that invokes a separate, non-artistic system of value, not unlike medieval religious icons, which were priced by both their devotional subjects and by the amount of gold they contained.) Finally, these pictures all have certain qualities—a chic strangeness, a mysterious drama, a meditative calm—that function well in the realm of high-end, hyper-contemporary interior design.

Another important element of Zombie Formalism is what I like to think of as a simulacrum of originality. Looking back at art history, aesthetic importance is measured by novelty, by the artist doing something that had never been done before. In our Postmodernist age, “real” originality can be found only in the past, so we have today only its echo. Still, the idea of the unique remains a premiere virtue. Thus, Zombie Formalism gives us a series of artificial milestones, such as the first-ever painting made with the electroplating process (Kassay), and the first-ever painting done using paint applied in a fire extinguisher (Smith). "

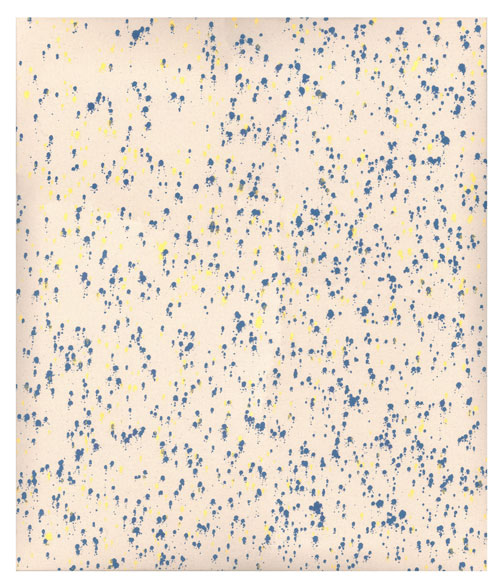

Robert Yoder, TD (HOBBY LANTERN 2), 2013

The term caught on and has been in discussion for the last few months. Oscar Murillo is name-checked in almost all of the articles mentioned, and is actually the artist I'm least offended by. His show at Isabella Bortolozzi Galerie was invested in using the space in a way I found interesting, and I liked his film and photo work much more than the mostly contentless paintings (which are what presumably have been selling for upwards of $400k apiece).

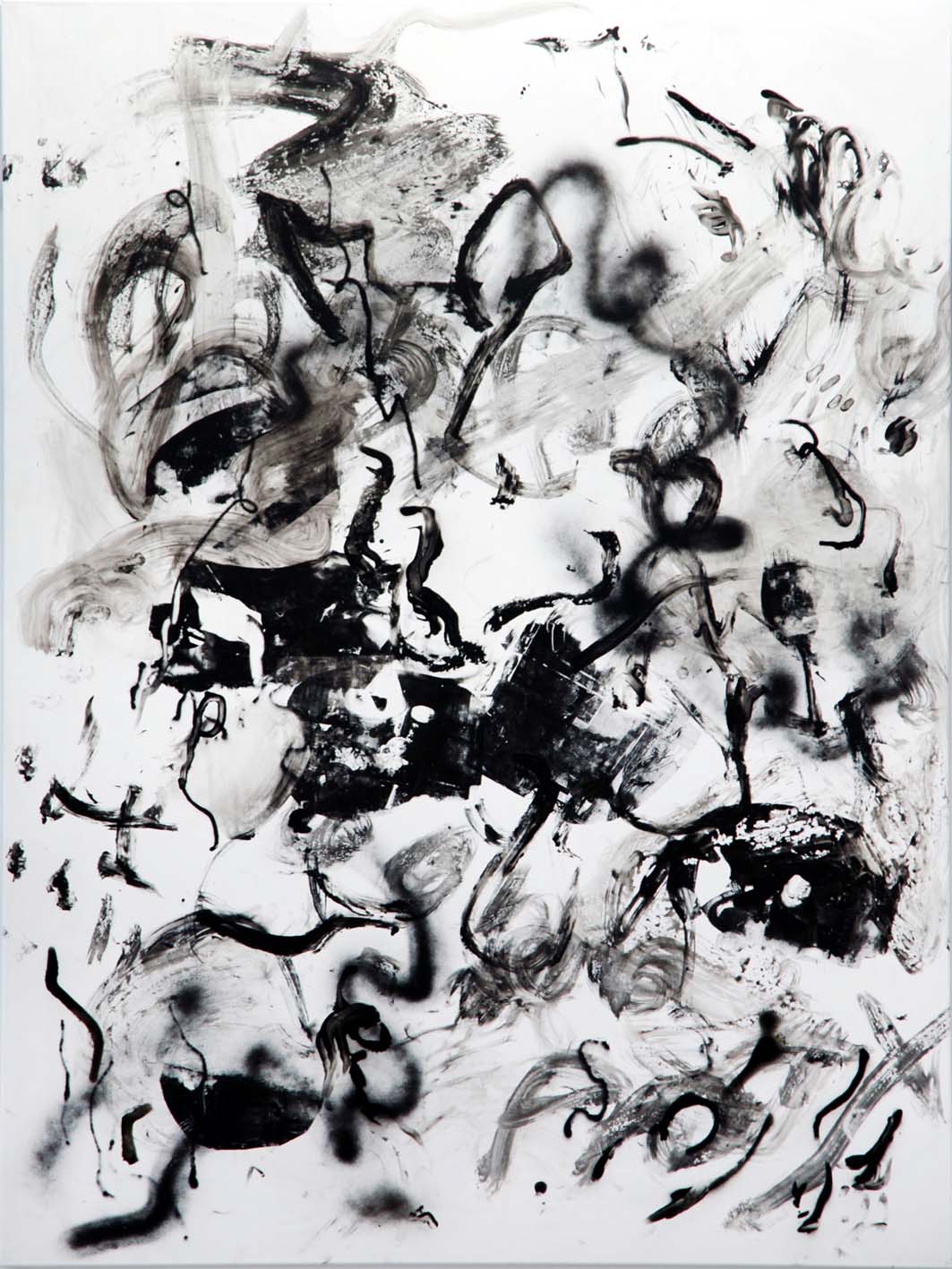

Oscar Murillo, Untitled (stack paintings), 2013

Jerry Saltz gets rude: "Galleries everywhere are awash in these brand-name reductivist canvases, all more or less handsome, harmless, supposedly metacritical, and just “new” or “dangerous”-looking enough not to violate anyone’s sense of what “new” or “dangerous” really is, all of it impersonal, mimicking a set of preapproved influences.

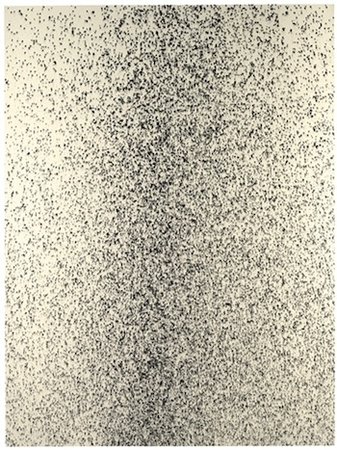

This work is decorator-friendly, especially in a contemporary apartment or house. It feels “cerebral” and looks hip in ways that flatter collectors even as it offers no insight into anything at all. It’s all done in haggard shades of pale, deployed in uninventive arrangements that ape digital media, or something homespun or dilapidated. Replete with self-conscious comments on art, recycling, sustainability, appropriation, processes of abstraction, or nature, all this painting employs a similar vocabulary of smudges, stains, spray paint, flecks, spills, splotches, almost-monochromatic fields, silk-screening, or stenciling. Edge-to-edge, geometric, or biomorphic composition is de rigueur, as are irregular grids, lattice and moiré patterns, ovular shapes, and stripes, with maybe some collage. Many times, stretcher bars play a part. This is supposed to tell us, “See, I know I’m a painting—and I’m not glitzy like something from Takashi Murakami and Jeff Koons.” Much of this product is just painters playing scales, doing finger exercises, without the wit or the rapport that makes music. Instead, it’s visual Muzak, blending in."

Here's a gallery of "Zombie Formalist" work. If you're interested, Jerry Saltz has compiled very interesting side-by-side comparisons of works of art by different artists that he feels reflect this trend. The article is very much worth the read. What do you think? Personally, this is a style or sub-movement of art that I found myself very disappointed by when visiting galleries. When many works of this kind are in the kind of proximity necessitated by a solo show, they become small, drab, homogenized- not the kind of thing I return to.